Years ago, I worked at a national historic site on Boston’s Freedom Trail. A frequent question of visitors was “How much of the building is original?” I knew what they meant by the question but sometimes I felt waggish (or was a smarmy asshole, depending upon your point of view) and would answer that it was all original—just not of the same era. As with many historic buildings, it was a patchwork, a collage, having undergone many changes before being “saved.” Then it underwent more adaptations, with well-meaning but naive or poorly-researched alterations over time in attempts to return it to its “original” state. At some point, they called it quits and either glossed over or foregrounded the hodgepodge state.

Questions of “originality” are close to but not quite the same as “authenticity,” though they sometimes are used interchangeably. They at least go hand-in-hand: the former denoting the latter. Why I relate the example of the historic site is for this connection but also because I see the notion of authenticity to be like the building. The concept of authenticity is a patchwork that is—and is about being—simultaneously consistent and an artifice.

Put into a graphic design context, authenticity is also a lot like notions of “neutrality.” Robin Kinross gave that concept a thorough and deserved thrashing almost 30 years ago in “The Rhetoric of Neutrality.” Authenticity isn’t as prevalent and active a design concept as neutrality was—and continues to be—but it shares aspects. The primary one is that both concepts have been imported from another realm. Metaphorically, the adaptation is intriguing. Functionally, we have to question the “rightness.”

Kinross outlined how the ideas of communication theory (such as the Shannon-Weaver model), which speculated about the efficient sending of radio signals, were grafted onto design theory. This gave rise to the idea of that the designer should be an objective “transmitter” of “information.” Kinross showed how this transplant was a product of an era with a rising, optimistic belief in technology and science. We know the critiques of the Shannon-Weaver model as applied to design: audiences aren’t homogeneous passive receivers; designers aren’t objective transmitters; and messages are abstract, active, and multiform.

Authenticity similarly was first concerned with another kind of determination—the status of an object: “not false or copied; genuine.” Objects can be put through an evidentiary analysis to establish veracity and value. In a music context, for instance: do I have an original pressing of this LP? Once again, we must make a conceptual leap to apply the authenticity concept not to the physical product per se but to the abstraction of the process that created it. Taken literally, every design or song is authentic on its actual face. But not, possibly, to your process requirements.

Authenticity—as abstract process evaluation—becomes another observer-oriented, relative experience. Like Einstein’s relativity, the authenticity experience runs on separate, internally-consistent, parallel measures. Instead of clocks, you have scales of sorts. Reconciling the separate spheres isn’t possible—there’s no overarching reality but the existence of the artifacts in question. But perceptions of them differ and they’re all true.

We can dip into the discrete authenticities. And it seems possible to cross between them—to become sensitized to another authenticity and embrace it. Exploring the different authenticities is worthy as it will tell us things about the permutations of culture. Crafting a unified field theory, though, is something else.

The popular conception of authenticity is a construct, a role. By necessity it is a well-defined, recognizable one. As in rap-related authenticity, the features are clearly delineated: jail-time for a drug or violence related offense, or an injury due to the discharge of a firearm with you as target must feature in your CV. But it’s an act (though in a bio-pic sense—”based on a true story”) that only gestures toward the real. Authenticity is superimposed, not arisen from the actor/performer’s life. Instead of an absence of artifice, popular authenticity is the ultimate artifice. Popular authenticity then provides an imprimatur to any product of the actor. The actual “music” is irrelevant. Popular authenticity doesn’t free music, it kills it.

This isn’t the only paradoxical inversion of chasing popular authenticity. What do we make of an artifact like 1974’s Having Fun with Elvis on Stage? This LP consists entirely of samples of surreally-edited, between-songs patter by the King. Is it the most authentic Elvis—dispense with the music altogether, it doesn’t matter—or the least as it evidently was a commercial “ploy” by Colonel Tom Parker to evade Presley’s contract with his label, RCA (they eventually released it). Lester Bangs referred to this LP in his famous eulogy “Where Were You When Elvis Died?”, citing it as a solipsistic expression of Elvis’ contempt for his audience.

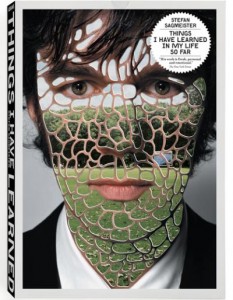

What has driven authenticity from product to process—and created a popular authenticity? Perhaps it is the result of a technologically enhanced estrangement from the musician. Recording technologies provide greater access to the product but, as popularity increases, less access to the artist. Contact is through the machinations of PR. Image-making, in the sense of a creative persona, is of the most importance. The search for “authenticity” is an attempt to negotiate the Spectacle‘s funhouse hall of mirrors.

Authenticity is popularly regarded as a centerpoint, a statement of tradition and stability. Authenticity can and should be returned to. However, as culture can’t remain static, neither can authenticity. It must always be a state of the new—simultaneously a transformational agent and response. Authenticity is not comforting and secure, it is a challenge and extreme. It shocks the system, reboots it, and runs a fresh program. Authenticity is a breakthrough, an advance beyond the encumbering popular authenticity—the static role—to a reconfiguration.

Authenticity isn’t a point, it is a wave front. A kind of carrier wave, transforming not transmitting the leading edge of meaning. Imagine the grooves of an LP, endlessly propagating, spiraling outward forever.

Authenticity is not the result, it is the cause.

Authenticity changes its nature depending upon the expression—formless in itself; the generator of form. Authenticity isn’t embodied within either the artifact or artist. Authenticity makes them, then moves on.