“I love rock and roll…I can’t get enough of it! But I’m really sad the way it’s gone. I find all the young designers…and I’ve talked to a lot of them…they think they’re doing Art, and they talk about record covers as Art. They do one sleeve and they are already talking about what they are going to do for the next album cover. All that to me is highly suspect because you’ve got to wait, hear the music and meet the guys, and they tell you what they want and then it’s up to you to deliver that.”—Barney Bubbles, The Face, November 1981

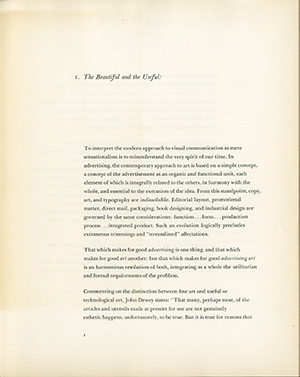

“I had begun to find it increasingly difficult to control the quality of my work and to develop as a designer unless I was working on a pro bono basis or for a minimal fee for a design organization or design-industry client. This was depressing because I believed that the whole point of graphic design was to bring intelligence, wit, and a higher level of aesthetics to everyday products, the articles of mass culture. I did not want to be an ivory tower designer; I had little interest in theoretical exploration. My goals were to design things that would get made, to elevate popular taste through practice, and to make graphic design breakthroughs on real projects.” —Paula Scher, Make It Bigger

What is certain is that Bubbles maintained a powerful working momentum in the circumstances—drunken visits from The Damned, Wreckless Eric and others, Riviera and Robinson roaring into telephones and the odd cider bottle flying across the office. Only once did he find the lively atmosphere intolerable. An over-refreshed executive—it may have been Robinson—failed to hit the target in the lavatory on the floor above Bubbles’ desk, and ruined artwork with splashes that rained down from the loose floorboards overhead. “Barney was absolutely hopping mad,” says Glen Colson…“He came out screaming and shouting about that, and quite right too. But it was very funny.”—Paul Gorman, Reasons to Be Cheerful: The Life and Work of Barney Bubbles

Barney Bubbles was a unique design talent in a discipline offering an array of singular practitioners. Placing him in context and characterizing his particular aptitude can be challenging. His specific practices—design of music industry artifacts, illustration, painting, video, furniture—weren’t exclusive. In this variety, he was representative of the classic Modern design sensibility of total design.

Coming of age in the early 1960s, Bubbles was representative of his generation in many of his pursuits and attitudes. He moved from the standard agency practice to design for and about the rising youth culture (translation: he became a hippy). Popular culture—music—was supplanting corporate identity as the young designer’s muse and preferred client.

Focusing in on Bubbles’ particular obsessions—and a serendipitous conjunction—reveals his affinity with a contemporary designer who shares a similar career path and sensibility. Not only does this comparison offer insight into both designers’ activity, it outlines wider import in how modern design tenets will diverge in application based on biography and geography.

Among American designers—if not overall—current Pentagram partner Paula Scher is Bubbles’ closest counterpart. Immediately, there’s a fundamental difference between the two: fame. Both do have one monograph apiece, though Bubbles’ is posthumous. Scher is an established, internationally-renown and extensively discussed (though hardly examined critically) figure in design. Though steadily gaining in recognition, Bubbles remains a discovery and reclamation project. During his career, he could only dream of a visibility that readily came for Scher. Some can be attributed to his idiosyncratic design agenda. More to the limited regard afforded at the time to sleeve designers in the broader field.

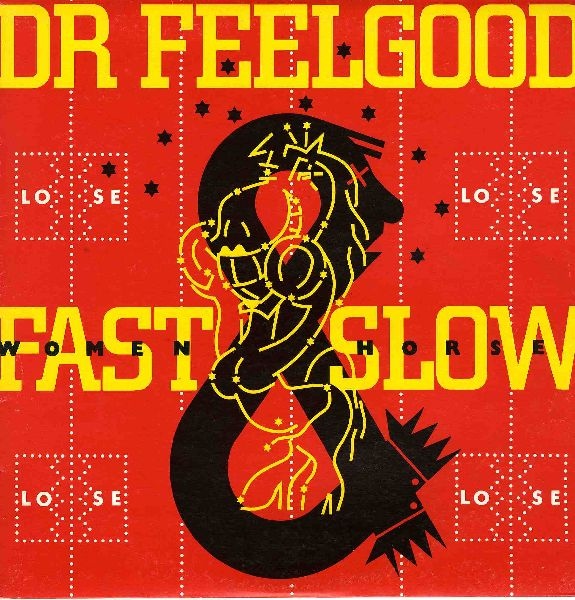

Bubbles designed for a variety of labels but worked primarily for small independents like Stiff Records and its offshoots. By contrast, Scher earned visibility while working exclusively for a major in her album design career. Their respective careers cross at Scher’s employer, Columbia Records, the U.S. licensee of Elvis Costello and Nick Lowe albums.

In salient aspects, Bubbles and Scher coincide. Both made their names in record album design in the 70s, their activity roughly contemporaneous. Where Scher went directly from art school into the CBS Records advertising and promotion department, Bubbles began his design career in agencies and freelance a decade earlier, with occasional (and award-winning) forays into poster design for musical events. Overall, their career paths were roughly inverted.

Bubbles’ first LP design was in 1969 (Quintessence’s In Blissful Company, Island); Scher began designing albums in 1973 at Atlantic Records, moving to Columbia in 1974 until her departure nine years later. Bubbles, tragically, committed suicide in 1984.

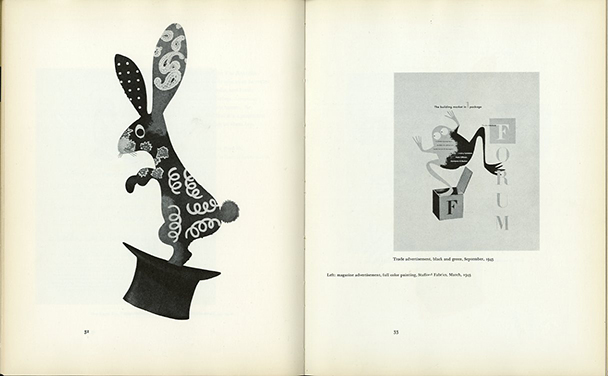

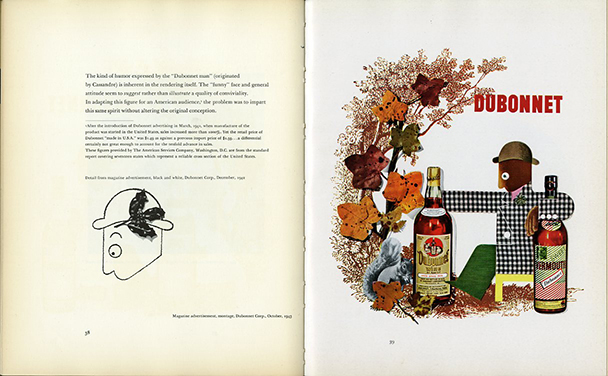

Most significantly, they shared fundamental creative influences and strategies. Each began their album design career emphasizing illustration. Bubbles was his own artist, while it was an opportunity for Scher to commission her preferred illustrators. Her concepts were fairly straightforward and “illustrative,” with a Big Idea verbal/visual twist—prevalent still in professional design. Heat Wave’s Too Hot to Handle (1977) features a Robert Grossman image of a giant Epic Records album melting on a scorching sidewalk; Yardbirds Favorites (1977) has a David Wilcox rendering of assorted birds on the front lawn of a suburban American home.

Due to servicing clients like Hawkwind and its offshoots, Bubbles’ illustrations could be more outré and reflective of the hippy lifestyle. Still, they were descriptive and products of the same general method. A sleeve such as Kursaal Flyers’ Chocs Away! (UK Records, 1975)—with a melting chocolate airplane soaring into the sun—fits easily alongside Scher’s projects.

Some Bubbles and Scher works appear that they might be in dialog across time. The cover of My Aim Is True and its Keith Morris photos seem to envisage Scher’s mid-1990s Public Theatre poster series. Both display black and white photographed figures silhouetted against bright flat colors. Costello, however, wasn’t dancing, but was being choreographed—by Bubbles. The designer stood behind the photographer, according to Paul Gorman, “throwing moves and poses behind the camera to inspire and animate the singer.”

Both displayed a fascination with and virtuosity at reworking historical and vernacular styles. While they grounded their work in their respective country’s graphic heritage, they readily and adeptly incorporated expressions beyond their indigenous borders.

Scher has consistently employed distinctly American type styles dating from the early years of the 20th century. Employing aspects of American Modern design was a hallmark of counter-cultural/contra-European Modern expressions championed in the 1960s. Push Pin Studios is the most notable example and influence cited by Scher. Her early work regularly employed Cheltenham as serif, Franklin and Trade Gothics for sans, slab serifs, or utilized typography derived from wood type.

Bubbles also drew upon American influences, though from later in the century, eventually favoring an active Reid Milestyled letterplay that expanded to conjure the pre-Beatles 50s and early 60s era of rock and roll. Otherwise, his type choices largely reflected his training at his first design job under Michael Tucker: “Very Swiss; very hard; unjustified; very grey.” However, as did Jan Tschichold, Bubbles leavened his copy with standards like Plantin and Garamond.

A disparity is that Scher will regularly pursue a wholly typographic approach. Though no less expert and inventive with type, examples of a Bubbles type-only treatment —such as the concrete poetry-inspired Xitintoday (Nik Turner’s Sphynx; Charisma, 1978)—are rare.

Bubbles and Scher’s confluence is at early European Modernism, particularly Russian Constructivism. The coloration and structure of Scher’s famed Columbia “Best of Jazz” promotion poster is the most renowned exponent of this influence, though eclectically fused with her favored wood type styles.

Bubbles referenced El Lissitzky’s “PROUN” paintings to churn out a sleeve overnight for Ian Dury’s 1978 Stiff single, “Hit Me With Your Rhythm Stick.” The Bubbles blender mixed in stamp kit typography and origami.

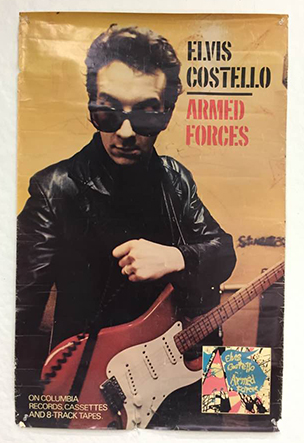

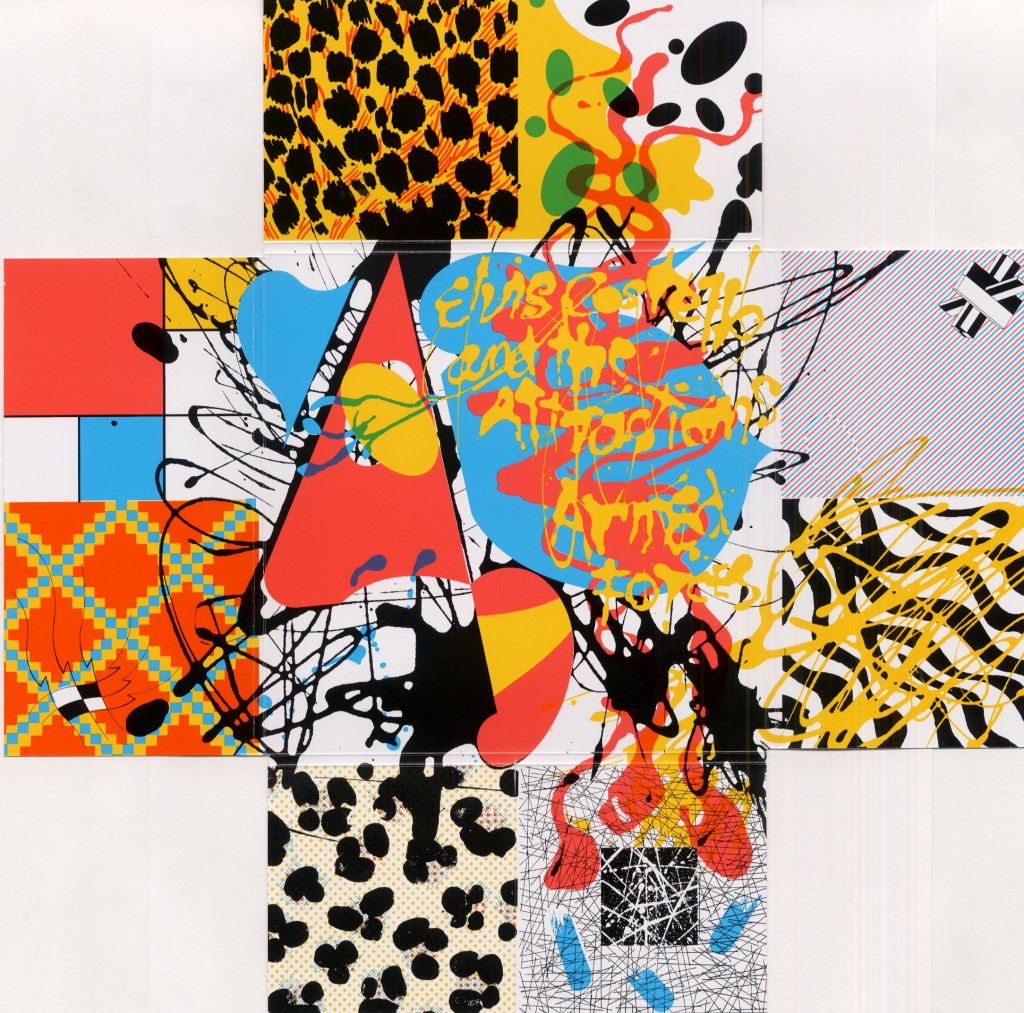

With the sleeve of Armed Forces (Radar, 1978), Bubbles manufactured a supercollider of high and low art allusions that condensed all his obsessions in one place. Scher has no comparable multiplex masterwork but, as with the “Best of Jazz” poster, produced tour de forces that drew upon single or fused references.

Foremost is her 1984 identity for Capitol subsidiary label Manhattan Records. Wisely steering her client away from representations of buildings, she intuited a flexible and practical identity based upon Piet Mondrian’s painting Broadway Boogie Woogie (1942–43). The artwork is composed of the familiar De Stijl primary colored squares but reduced in scale and lacking the framing black grid. According to the Museum of Modern Art gallery label, “These atomized bands of stuttering chromatic pulses, interrupted by light gray, create paths across the canvas suggesting the city’s grid, the movement of traffic, and blinking electric lights, as well as the rhythms of jazz.”

Among the brew of art samples Bubbles splashed on the inside of Armed Forces is a segment of the classic Mondrian composition. Scher focused entirely on a later manifestation of the approach. Her identity reverberates visually and conceptually across multiple levels. Dovetailing together is a visual reference of music that also symbolizes the streets of New York.

While the formal aspects of Constructivism were a mutual, predominant attraction, for Scher the choice was always “pragmatic.” The “vaguely constructivist look” of the “Best of Jazz” poster happened because she was “rediscovering El Lissitzky and Aleksander Rodchenko at that time.” She was (and is), however, far from apolitical, evidenced by examples of opinionated work on a range of topical issues throughout her career.

Bubbles engaged the political ideals on another, personal level. On his self-titled blog, artist and Bubbles schoolmate David Wills writes: “The great Russian artist El Lissitski (sic) was a big influence on Barney’s work. … Barney later called El “a hack” – but as I said, I suspect that was because El later buckled under Jo Stalin and became another Social Realist doing what he was told, something Barney always fought against with all his might.”

♦

Another shared feature is the use and treatment of information design and data visualization. Both conspicuously utilize charts and graphs set to serio-comic ends. The two designers have it both ways: the “neutral” design form conveying both rhetoric and fact. Absurdity, rather than clarity, is foremost in the content of the graphics and the decision to use the form. They become profoundly apt in exposing their often-farcical topics. The cool detachment heightens the irrationality.

With Bubbles, it’s another episode of drawing attention to and disrupting the tropes of graphic design. He exposes the ploys while indulging in them. This may derive from a vacillating view of the value of graphic design. Layered on top of this is his similarly conflicted view of popular music. Bubbles highlights both the romance and reality of the rock and roll life for performer and audience. His devotion to the ideal of the music goes hand in hand with disclosing its disposable artifice. Graphic design is correspondingly ephemeral and profound.

In his interview for The Face in 1983, Bubbles stated, “I find it’s a big racket. I think everybody should own up, first of all that they’re doing it for the money and the art definitely comes second. All it is is rock and roll and it’s no big shakes. But at the same time I think commercial design is the highest art form.”

The two sides of the inner sleeve of Nick Lowe’s first solo album, Jesus of Cool (Radar, 1978), expose these conflicts. One side offers a graph of “The Artiste At Work,” over a monotone image of meshing machine gears. The horizontal scale details a chronological listing of Lowe’s output as band member, producer, and solo performer. The left hand vertical legend captions a steadily rising numbered scale: “Creative productivity output extrapolated from estimated work hours against an inverse ratio of critical acclaim.”

This is countered by the right hand caption for a sharply downward trending segmented line: “Actual analysis of product showing negative sales potential allied to public avoidance factor.” The satirical take on the lingo of A&R men echo the narratives of album tracks like opener “Music for Money” and “Shake and Pop.”

On the reverse side, a photo of a gymnast, frozen mid-leap, head circled, is labeled “The Artiste At Play.” The completion of the work/play adage is the closet to sense the graphic makes, with its image a dubious representation of the “artiste” and the activity an improbable leisure pursuit for a refurbished pub rocker.

The inner sleeve of Johnny Moped’s Cycledelic (Chiswick, 1978) hews closest to the Modern intention of the information graphic form. Here he adopts the format of Peter Frame’s “Rock Family Trees” to detail the band’s lineage. However, though the graphic plays it straight (earning praise from Frame for improving on his concept) Bubbles sees fit to disturbingly set it over a photo of troops arrayed at a Nazi rally.

Other incidences result from an uncomplicated design ideation but with Bubbles’ inventiveness shaping the result. Following its technological source, Bubbles devised a graph graphic for the logo and label of Radar Records. Eschewing the obvious sound waves, he creates a ‘scope displaying signal pulses that spell out “radar.”

The graphics of the inner sleeve of Elvis Costello’s fourth album Get Happy!! (F-Beat, 1980) offer no edifying data. On the front, three ellipses represent “Big Man,” “Tall Man,” and “Extra Wide Short Man” with type scaled and weighted according to the description. The portrayal resembles a children’s book page, or a basic expressive typography demo. Tying into the album’s title, the obverse offers the “Happy Man,” intersecting ellipses arrayed in an “atom” shape.

Incidences of infographics tail off in Bubbles’ later years. The entirety of the front cover of Wang Chung’s Points On A Curve (Geffen, 1982) is given over to a graph in a rare example of literality (save for the enigmatic Brian Griffin cover photo). And for the back of Billy Bragg’s Life’s A Riot With Spy vs. Spy (Utility, 1982), Bubbles anthropomorphizes a graph that updates a World War II propaganda poster: “Beware the Squander Bug” (which on the record’s label, is captioned “A Ration of Passion.”)

Where Bubbles made information graphics an occasional element in his sleeves, Scher’s applications emerged after her album career. (Her current cartographic paintings extend this interest into another medium.) Even if absurd in content, her use is strategic, never wandering into the surrealism of Bubbles’ specimens. Her focus and wit are keenly fixed.

An early effort is the cover of the 1985 Print magazine parody issue: “The Complete Genealogy of Graphic Design.” More Monty Python than Phil Meggs, the chart rambles through a bizarre cataloging of historical figures, most unconnected to the field. Arrows and dashed, solid, or squiggly lines suggest connections or couplings between unlikely figures: Herbert Bayer and Queen Elizabeth II seem to gotten busy (or something). If there’s a commentary on graphic design history, it’s decidedly elusive: “The whole insane chart moved through history until it ultimately arrived at Milton Glaser.”

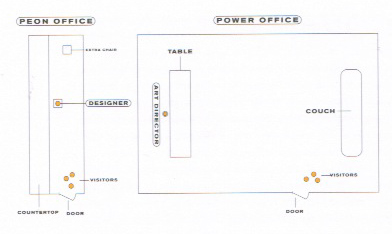

In Make it Bigger, Scher makes diagrams a central element of the text. She provides them throughout in a serial explication of her central thesis that “judgments made about graphic design…often have little to do with the effectiveness of a given design in the marketplace and more to do with how human beings naturally behave in complicated hierarchical social situations.”

At first, the diagrams are functional tinged with humor: illustrating the approval processes at her workplaces, or contrasting “power” and “peon” office set ups. She then proceeds into more subjective—and astringent—presentations such as “Diagram of a Meeting” and “Personality Types in Combination.”

Unlike Bubbles, Scher isn’t struggling with or exploiting any contradictory impulses in her design. Ambiguity is the enemy of effective design. With her no-nonsense manner, Scher debunks any romanticism in the creative process. Much of the book’s text describes how worthy design is prevented: conditions related to the thesis above. Eluding them is the key—either through haste (rush jobs that short circuit the process) or indulgent clients (jazzers, mostly).

“Bob James was my first ideal client,” writes Scher of the musician and founder of Tappan Zee Records, “His was the only approval necessary…” Bubbles couldn’t agree more: “It’s just fun working with Jake (Riviera), we’d just walk around the block—‘cause he was so busy—it would all be done in five minutes. I could actually do what I wanted to do without being told off by the record companies that say: ‘Fantastic, but don’t you think…?’ and then they fuck it up!”

Arguably, Bubbles was allowed greater creative latitude in his situations. Major labels are risk- and cost-averse while the upstarts trade on the novelty of exotic packaging. Even as the company that, with Alex Steinweiss, pioneered the idea of album cover graphics, Columbia was staid and corporate.

Bubbles’ inventions were regularly bowdlerized or replaced in the U.S. (as occasionally were the musical contents of the albums). That Columbia was the U.S. distributor of a number of Bubbles-designed albums amply demonstrates the reality. If Scher had any awareness of Barney Bubbles, he would have served as a cautionary tale.

Scher’s is dead on in her analysis that the true determinants of design results are interpersonal dynamics and individual personality. Pushing distinctive design through the Columbia bureaucracy was likely a chore. However, she extrapolates this to all labels and fails to turn her jaded eye on herself.

Understandably, she attributes herself only the purest motives: “Money was irrelevant. It was more important to make uncompromised work.” There’s no reason to doubt her. But other motives go unspoken that play into her experience. One is plainly stated at the outset of her book: “Designers want to make things, or make things up, and have those things that they’ve made up seen, used, and appreciated by lots of people.”

Scher omits an important diagram that would complete her presentation. It should describe the inverse relationship between “uncompromised” and “lots.” In choosing to work for Columbia, she made a priority of the latter, depressing the likelihood of the former. Other labels, even other majors, offered greater creative freedom. Warner Bros.’ catalog was home to a variety of offbeat and artistic sleeves. Even Atlantic, the label she left for Columbia, issued sleeves that boasted “intelligence, wit, and a higher level of aesthetics.” But, in another unstated but crucial factor of the equation, they might not be of Scher’s aesthetic.

Other indices on the missing diagram probably should include geographical preferences. Working for Warners would likely require Scher living in L.A., which may be akin to a matter/anti-matter collision. And—though she excoriates it—a taste for corporate life. Stuffy as it may be, the corporate workspace was comparably sedate and neat. Scher may wryly depict the “peon” office she sought to escape—as described above, Bubbles literally labored in a “pee on” space.

Life is a series of trade-offs or compromises. Scher’s determination to defy this actuality is her defining trait. But where her otherwise refreshingly sober view of design activity lapses into fantasy is neglecting to account for this reality: choices must be made. Everything Scher says about the stultifying nature of corporate design is irrefutable. But the ultimate barrier isn’t the system, it’s the designer’s—her—choice of where to labor.

Bubbles likely recognized the trade-off and struggled with it. The Wang Chung commission got him a visible (hit single) major label job. But Points On the Curve ranks as one of the least interesting works in his oeuvre. While still avoiding the default cliché of sleeves—the band portrait is relegated to the back—it’s a disappointing effort. But when he makes something distinctive for a major—like The Psychedelic Furs’ Forever Now (CBS, 1982)—he only sees it get replaced with a New Wave cliché in the States.

Logo design is another difference between the two. Logos seemed to flow effortlessly out of Bubbles, all equally ingenious, no matter how spontaneous (“I phoned him and said, ‘I want a logo. It’s got to be black and white and square,’ Dury told Will Birch. ‘Then I heard somebody in his office say, ‘Wow’ and he said, ‘I’ve done it!’”)

He also deliberately fashioned more marks than he needed to (and probably was paid for). For both Stiff and F-Beat, he bespoke an array of marks that suggest a restless imagination or an abhorrence of design doctrine. However, they were masterful components of the labels’ brands and players in the larger identity game Bubbles was playing.

Scher is brief and self-effacing on the subject of logos: “I appreciated clever marks that had strong, simple, positive and negative shapes…but was never capable of designing them.” She states her preference for typography-based marks, such as the Manhattan Records logo. And though she discusses her Tappan Zee Records identity, its logo is neither reproduced nor mentioned. If it was Scher’s creation, it contradicts her evaluation of her facility with form.

♣

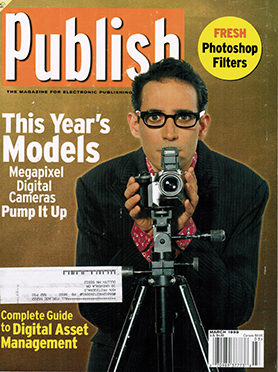

If Bubbles has an iconic cover image, one that transcends its specific usage, it may be Elvis Costello’s second album This Years Model (Radar, 1978). Costello’s confrontational, table-turning stance became a symbol of the post-punk era, which preserved the provocation of punk while broadening its sonic palette.

At its core, the image is a direct conception of the record’s title and its source songs, a contraction of “This Year’s Girl,” and the “she’s last year’s model” lyric from “(I Don’t Want To Go To) Chelsea.” Putting the artist on the cover is the no-brainer design strategy. Bubbles complicates the reading by extending Costello’s aggressive, anti-rock star poses from My Aim Is True. The U.S. version goes all-in in defying expectation, with the artist largely obscured, crouched behind the camera, peering over it at the viewer.

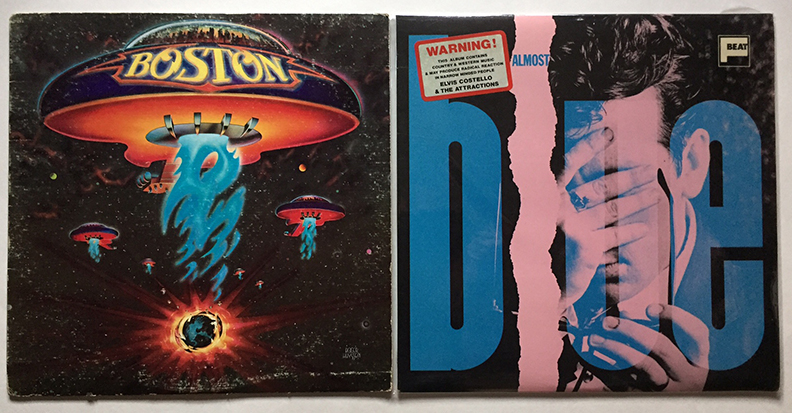

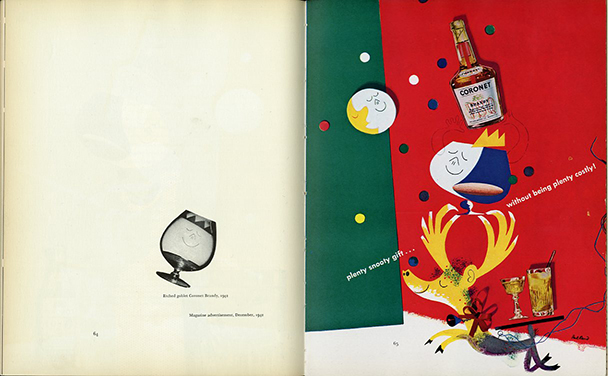

Scher’s most recognized cover is one she regards mordantly: the mega-selling eponymous first album of the group Boston (1975). Its appearance in Make It Bigger has the flavor of a musician dutifully but reluctantly performing a throwaway track that became a novelty hit. Scher gamely relates the gestation of the Roger Huyssen cover painting, perplexed at its ultimate ascendance to iconic status.

Of both the music and sleeve, Scher is dismissive: “Musically Boston is not a great album. “More than a Feeling” is decidedly mediocre, and so is everything about the album package, but it struck a chord with sixteen year-old boys and their girlfriends in 1976.” Even were I not of that specific age group at the time, Scher’s trivializing of an audience sounds snobbish—and commercially antagonistic. Aren’t sixteen year old boys and their girlfriends deserving of attention? More importantly, isn’t that a substantive chunk of the popular music market?

Scher is too savvy to not recognize “the strange chemistry and karma of hit music. Hits don’t really have anything to do with qualitative decision-making or careful planning. Genius or originality don’t guarantee hits; you can’t even rely on predictable, salable mediocrity. Hits are happenings in a particular period of time that manages to capture the imagination of a large but specific audience in a specific and personal way that defies all logical explanation.”

The lesson to and frustration for the graphic designer is that you can replace “hits” with “great graphic design” and it’s just as accurate.

For that 16 year old me (and now, actually), Boston was an amusing trifle that I felt warmth for because of its hometown origin. And though musically it was the antithesis of the punk and new wave I was bonding with, it was a scrappy anti-corporate move. The record was a basement-made, against-the-odds triumph of Tom Scholz, a moon lighting Polaroid engineer. That is so rock and roll. The sleeve was silly but what do you want?

By all measures, Scher nailed it with Boston as she did with no other sleeve. Her account of the hushed awe that greets her introduction as its designer verifies its power. The sticking point is that in her greatest success as a cover designer, Scher was simply a facilitator of the client’s “idiotic” idea. And the client was right. That is not supposed to happen. I can only imagine Scher thinking, If only that blockbuster had my design instead of that “stupidity.”

Barney Bubbles, who mined kitsch without irony, would be at peace with such a notion. A fleet of city spaceships vaporizing planets would be another day at the office for the guy that illuminated his own zany Space Ritual. He got it: “All it is is rock and roll and it’s no big shakes.” Rather than dropping the quality of sleeves with this attitude, he elevated it.

♠

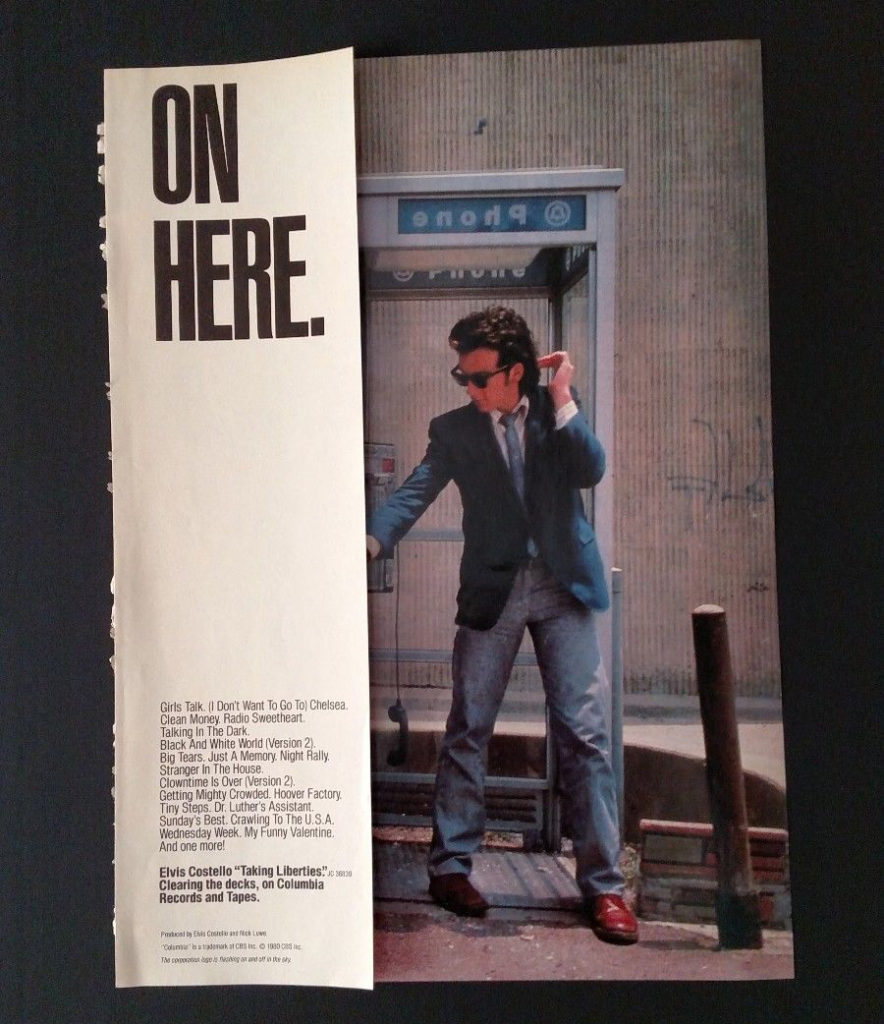

The Bubbles/Scher Venn diagram overlaps at Elvis Costello. Two artifacts cross over and demonstrate the designers’ affinities and departures: the 1980 U.S. compilation album Taking Liberties, and a Trust promotion poster.

Taking Liberties was a compilation of tracks that hadn’t seen release in the U.S.: either U.K. single A and B sides, or album tracks deemed “too British” by Columbia and removed or substituted. Its release came on the heels of Get Happy!! and sought to capitalize on the proliferating import market. In a clever reference, its title comes a lyric on the included song “Crawling to the U.S.A,” which satires American cultural domination.

Compilations represented a rare opportunity for Scher: “Repackages were generally nonpolitical album covers,” she writes in Make it Bigger, “antidotes” to the wrangling that occurs over new releases—bones thrown to persecuted designers.

Beyond her position as art director, it’s unknown how involved Scher was with the design. The densely set Franklin Gothic text is a Scher hallmark, along with its unfussy layout. Rather than commission an illustration or craft a total departure, the covers seems a concerted attempt to relate to some of Costello’s previous releases. A 1979 Brian Griffin photograph of Costello in L.A. (which also yielded images that adorned Armed Forces and its attendant Live at Hollywood High EP) wraps around to the back of the sleeve. The picture has been inverted so Costello reaches to the left to grasp the noodly line spelling out the title.

In upper left hand corner of the cover, the artist’s name is spelled out all caps in a super bold sans serif face. The scale of the type and its tri-coloration are nods toward prevalent new wave stylings. Overall, the sleeve is tasteful, functional, and ordinary.

The lone gesture to the conceptual play of Bubbles’ sleeves is the disc label. Adapting a design from the 1920s, the word “Columbia” is replaced on one side with “Costello.” Though Bubbles regularly invoked and evoked period design styles, the impact here is blunted by the age of the sample. It predates the musical eras Costello channels in his music. Later designs would have been both conceptually and graphically more representative and interesting.

But the genuine Bubblesian meta-move doesn’t come from the designers or is part of the album package. For the print ads, the text “And the corporation logo is flashing on and off in the sky” is placed underneath the legal text at the bottom. The line is from “Night Rally,” a song excised from This Years Model and included on Taking Liberties. Was someone in PR hip to Barney?

The more prominent and telling intersection is a poster for Costello’s 1981 F-Beat album Trust. Scher features this work in her book, the result of successfully lobbying for oversized posters—an instance where she wants to make it bigger.

Source material and time are scant for the project. The Brits only provide a “grim” Photostat of an image intended to be the “back cover” (it’s actually the front). Scher remains incurious about the source of the image. No credit or attribution is provided. It’s a still from a Bubbles-directed video for album track “New Lace Sleeves,” with a closeup of Costello’s head and shoulders. Head tipped downward, Costello stares up over his horn rims. For the album’s cover, Bubbles cropped the image and placed a handwritten title in the upper right hand corner. It’s the shadow of Costello’s specs on his face that grabs Scher’s attention.

To mask the poor quality of the image, she pumps up the scale and the hue saturation. Perhaps as an unconscious gesture to the (musical) New Wave style of acid bright colors (Scher avers she can’t provide a specific rationale for the choice), she fills the lenses of Costello’s glasses with solid hues of red and blue. The portrait is bracketed top and bottom with the text TRUST ELVIS in the manner of a campaign poster. “Costello on Columbia” sprouts from Costello’s left ear. All type is in Scher’s preferred call-back slab serifs with the ear-emergent text set akin to a broadside.

Scher’s proof for the poster’s success is its subsequent widespread in-house theft when delivered fresh off the press. The volume of larceny executed by record company employees could be considered a measure of validation (where’s the diagram for that?) but is hardly authoritative. And fetching high prices as a collectable is similarly problematic. If sticky-fingered Columbia cogs snapped up the majority, scarcity could be the driving force. These rationales also don’t affirm of Scher’s original argument for the oversized poster: that shops would clear space for such a product. Did they? Maybe none were left.

As a Costello fan at the time, I was aware of the poster and didn’t care for it. It possessed none of the smart, feisty energy of the music or graphics of the U.K. releases. Its coloration seemed affected, a cynical designer’s sop to New Wave fashion. The typography was incongruously “American” and “soft”—it felt more suitable for label-mate Billy Joel. Altogether, it made a dynamic performer bland and routine. Then again, maybe my desire was sated because I possessed an Armed Forces promotion poster, gifted by the owner of my local record store.

I agree with Scher that the poster is “well designed.” Considering the standards of her work, that’s hardly a concession, more a recognition of the obvious. Today, it’s desirable to me, but because of its provenance. The poster is the same but I’ve changed; it’s acquired new meaning. But while I admire it, I don’t love it like practically anything Bubbles might have done.

Reflexively, I try to attribute this to something in the design and not in me. As always, I blame Modernism. Its intellectual framework still suffuses our minds and insists everything resides in the object. But sometimes that object stars metropolis-bearing guitar spacecraft and everything goes haywire.

Looking into the designer only gets us so far and isn’t definitive. Bubbles loved rock and roll, a capricious but potentially indulgent client. His designs aspired to rock and roll in form: resonant, indulgent, transgressive…and merchandise. Scher preferred jazz and other less commercial musics. The artists were less image-conscious and open to illustration. They got out of a designer’s way. Rock was messy.

For Scher, sleeves were just another “everyday product” to bring a “higher level of aesthetics to.” Bubbles also endeavored for the latter but the former would be a gross simplification. He had abandoned the everyday product to embrace, for him, a higher plane of product. Albums had a special meaning for him.

It’s a truism that a designer’s personal engagement with the subject can result in better design. Bubbles obviously was more invested in rock and roll than Scher (I can’t track her personal taste at all from Make It Bigger). But any attribution of that as a deciding factor is belied by all of Scher’s consummate work for a variety of other cultural clients. All seem to have as much of her attention as any other.

And while the music didn’t mean as much to her as it did Bubbles (who played in bands and issued his own album), album covers did. Intriguingly, Scher cites three successive Beatles albums—Revolver, Sgt. Pepper, The Beatles—as emblematizing all design: “Everything everyone ever needed to know about graphic design was in those three album covers.” As exquisite as her taste is, it’s ironic that none are the work of a graphic designer.

Two are famously by contemporary British fine artists—Peter Blake and Jann Haworth for Sgt. Pepper, Richard Hamilton for ‘The White Album,” and Klaus Voorman—long-time band friend, artist and bass player—illustrated the front cover of Revolver. None follow the deliberate design process Scher adheres to. (Though “The White Album” arguably might to a degree. Hamilton’s proposal for the stark white cover was in deliberate contrast to the florid psychedelic fashion of the day—a strategic design move displaying an awareness of the marketplace.) Even if the concept/sketch/execution stages were followed, the decision to turn to fine artists and not graphic designers set them apart from the norm.

In his process and product, Bubbles seems closer to the spirit of these iconic sleeves. His works could be startling blends of unexpected imagery and eccentric interpretations of commercial imperatives. The variable covers of My Aim Is True and Do It Yourself were Bubbles own skewed updates of the editioned “White Album.”

♥

Scher’s covers are textbook examples of contemporary professional graphic design process at its best. Every step is exacting and the result highly polished and fluent. In her employ of top illustrators and photographers, Scher’s sleeves were like the many popular records they housed, featuring top session players recorded in the best studios. Results were consistent and flawless.

For some, this was something to rail at: “…all those other faceless LPs involving this floating crap game of technically impeccable hacks,” spat Lester Bangs in 1975. This attitude provoked another music, and another design, that valued spirit over proficiency. Or, more accurately, fostered a different definition of skill.

Scher was, and remains, an exemplary practitioner of the established conception of design. Bubbles expanded that model in every direction. They each served their clients well. And the audience? As John Lydon chanted, “This is what you want, this is what you get.”

Despite abundant and exemplary work in the area, Scher isn’t usually included in the roll call of major cover designers, not the way Bubbles is. The reason may be that it was a short prologue to a long and distinguished design career. She quit Columbia and seldom looked back (you should have kept the original, ladies).

Considering the wonders to come later, this stands a major what if. Sleeves designed by the creator of the Public Theatre posters or Ballet Tech would have been epic. However, reading Scher herself, they may not have been possible within the contexts she chose to work. Leaving album design apparently was required for Scher to fully realize her design vision.

Though Bubbles anticipated his departure from album design in his later years and expanding into new areas, it wasn’t by choice. He expressed regret about being supplanted by younger practitioners. “They’re so creative—the kids that do the sleeves—it makes me feel so staid and boring, and I think: I’ve got to get out, it’s time for me to go.”

This is another facet of attitude: Bubbles was reflecting his client industry, not his profession. Rock and roll was a young person’s game. At 39, he was a dinosaur. This could only be exacerbated going through the crucible of punk and it’s past-rejecting ethos. Only through ferocious talent had he escaped scorn for his hippy origins.

Of course, Bubbles’ potential beyond record covers will be the most profound what if. On his own, the early death makes the heart ache for what was never realized. For me, Paula Scher’s masterpieces come after the cover career, in a steady upward trajectory of achievement. Many can’t be predicted from what came before, which is only testament to her talent. Bubbles, despite his apprehension, showed no sign of his talent slacking. Comparing Bubbles and Scher heightened my appreciation of both. And sharped my sense of loss. Damn you, bless you both.

∞

Note: This is the second part of my ongoing study “Barney Bubbles: Offset Identities,” the first part of which is the previous entry in the “Writing” section. Both of these essays (and those to follow) owe a debt to and draw from Paul Gorman’s book Reasons To Be Cheerful: The Life and Work of Barney Bubbles (Adelita, 2010) for details and quotes about Bubbles’ life and work.