“Most of you won’t like this, and I don’t blame you at all. It’s not meant for you.”

—Lou Reed, original liner notes to Metal Machine Music (The Amine β Ring) (RCA, 1975)

♭♭

For Barney Bubbles, ersatz is as real as fake gets.

Due to his myriad puzzles and conundrums, it’s tempting to look for a skeleton key to Bubbles among his diverse productions. Is there a deciphering work? There are masterpieces such as Armed Forces that showcase most aspects of his design imagination. And for that sleeve, he even placed a self-portrait inside center.

The written record is thin where he speaks directly about his work. And when questioned, he manages to be simultaneously forthcoming and evasive. Most artists profess to speak through their work and Bubbles labored to leave us little else.

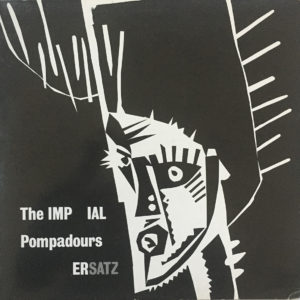

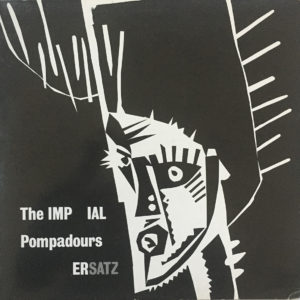

We do have a vinyl record that’s thick with meaning. The best candidate for the definitive Barney Bubbles work would seem to be his own and lone album Ersatz, released in 1982 under the moniker The Imperial Pompadours. Issued on an F-Beat one-offshoot imprint also called Pompadour Records, Ersatz inverted a concession made to select performers.

Labels frequently pander to their superstars by allowing them to create their own cover designs, regardless of their objective skill at design or illustration. (You tell Bob Dylan how ghastly that painting is, Mr. A&R Man.) Flipping the script enters the realm of the commercial unnatural for a major label.

Of course, such eccentricities were a regular feature of Bubbles’ chief champion and sponsor, Jake Riviera. Issuing an album by the label’s primary sleeve designer, even pseudonymously, is a prototypical perverse move. For instance, in 1980, Stiff Records issued the one-off joke album The Wit and Wisdom of Ronald Reagan. A shadow release attributed to Magic Records (“If it’s a success it must be Magic!”), the LP sported grooved—but silent—tracks.

Bubbles’ record should be filed with the 1982 promotion-only F-Beat LP, The Art of Roger Bechirian, Vol. 1. That album was a compendium of songs shepherded to disc by the ubiquitous engineer/producer (there was no volume two). It also featured an Alex Steinweiss homage sleeve design by Bubbles.

In his introduction to Paul Gorman’s Reasons to be Cheerful, Billy Bragg says how Barney Bubbles seemed like another member of the band. However, as simpatico and necessary as Bubbles may have been to those musicians, he was never regularly afforded such credit. Still, non-instrumentalists occasionally received equal billing alongside players. Lyricist Bernie Taupin got props from Elton John and Procol Harum’s Keith Reid was listed as band member.

Bubbles’ circumstance has similarity with another non-performing figure, Peter Sinfield. For his “words and illumination”—lyrics and stage lighting—Sinfield was accorded full member status beginning on King Crimson’s 1969 premier album In the Court of the Crimson King (which, upon its release, music critic Robert Christgau dubbed “ersatz shit.”)

As that group dissolved and reconfigured over their first four LPs, his role expanded to co-producer and noodling with a synthesizer off stage. When Sinfield was ultimately on the outs, he released his one and only album Still in 1973, on Emerson, Lake and Palmer’s Manticore label. Lake was another original member of King Crimson, and the record had contributions from other former and current personnel.

Bubbles’ closest and longest relationship with a band and its offshoots was with space-rockers Hawkwind. As influential as he was, the group never included Bubbles in their ranks. He is only one of six names listed on the sleeve of X in Search of Space under “optics/semantics,” which echoes Sinfield’s acknowledgement. Though arguably more distant from the action than Sinfield, Bubbles’ band buds supported his own venture into recording.

♭♭

Ersatz is a concept album, though not in the usual rock music sense. There isn’t an ostensible narrative running through and connecting the separate songs. Instead, Ersatz manifests themes of eccentricity, obsession and substitution graphically and sonically. Layered on top is a fixation on World War II, an experience that though not lived, permeated the consciousness of Britons of Bubbles’ (born in 1942) generation.

“Ersatz” is a German term meaning “substitute.” Inherent in the word is the suggestion of wartime goods. In the face of deprivation or scarcity, alternatives were fashioned. Coffee is brewed out of roasted acorns, tea from catnip. The connotation is of inferiority—bad goods.

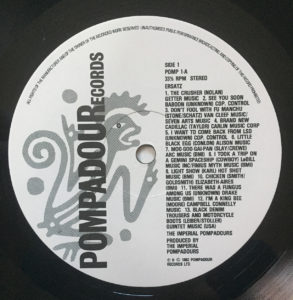

Apropos for a sleeve designer, Ersatz is an album primarily of “covers,” songs first performed by others. In a way, the album is, in its construction, a précis of Bubbles’ music-related career. With 13 tracks, the first side echoes the punk/post-punk style, which specialized in large groups of snappy, short songs.

Recent precedent existed from 1978 with Wire’s 21-track debut Pink Flag or the 1980 Bubbles-designed Get Happy!! which sported 20 total tracks, ten to a side. The Ersatz verso presents a single, side-spanning track—reminiscent of a extended Hawkwind space epic.

The album’s first side of cover tunes fulfills the replacement aspect of the title, declaring its own product to be a poor alternative. The songs are misfits to begin with, culled from the fringes of rock and roll’s early days. They’re affectionate piss-takes on novelties that were fairly alimentary to begin with.

Provenance isn’t a concern: three of the tracks are credited to “(Unknown).” The most notable of the songs are still obscurities, known for being re-recorded by prominent bands. “Brand New Cadillac,” appeared three years earlier on The Clash’s third LP London Calling. In 1981, The Cars demo-ed a version of The Nightcrawlers’ 1967 minor U.S. hit “Little Black Egg.”

Among other topics, tunes extol standard rock and roll subjects like Chinese food (“Moo Goo Gai Pan”) and detectives (“Fu Manchu”), space probes (“I Took a Trip on a Gemini Spacecraft”), psychedelic drugs (“I Want to Come Back from the World of LSD”), and…fungus (“There’s a Fungus Among Us”). Many of the originating bands hail from the States, home of millions of garages and attendant rock aspirants. Though numbered as discreet tracks, the songs blend and bleed into each other.

Bubbles wasn’t coy about his intentions with the record. According to Paul Gorman, he declared to a friend that the music was “inspired rubbish, loud and in extremely bad taste.” There’s plenty of operative bands that flaunt that attitude, but anyone hoping for an anglo-Cramps is setting their expectations far too high. Bubbles scribbled out some rough outlines—a full-fledged framework would be too confining—and let his collaborators fill them in. Lurching outside the sketchy borders was encouraged. Anyone in the studio at the time was invited to bang along.

Though steeped in humor, Ersatz isn’t a novelty album, as it contains performed and/or assembled compositions. While the performances and “arrangements” fall decidedly on the anarchistic end of the scale, it isn’t due to a lack of ability on the performers’ part. Bubbles deliberately mixed sawdust into his musical bread.

The record was assembled from sessions Bubbles had occasionally directed and participated in with sympathetic musicians—primarily Inner City Unit, saxophonist Nik Turner’s post-Hawkwind band. The performers’ proficiency was deliberately hampered by Bubbles’ method. Musicians were given lyric sheets and a single listen to a tape of the songs they were to play.

Bubbles also performed for the record and was a competent musician in his own right. Recalling their mutual Twickenham College of Technology days, former Small Faces keyboardist Ian McLagan said Bubbles “was a huge fan of Big Bill Broonzy and could play pretty good gut-string guitar in that folk blues style.”

The first side of Ersatz features songs with basic guitar/bass/drums rock accompaniment on each track with coloring provided by sax, piano, and organ. Performances are sloppy, by turns hung loose or studiously exaggerated. Every instrument will occasionally stray from regular order, becoming assertive or wandering off on its own. Drums follow a steady rock or tribal beat. The bass keeps to its lane, usually in sync. Vocals are spoken, shouted or comically-voiced.

Sometimes the vocals and instruments will be adorned with echo, evoking 50’s era rock and horror movies. Inserted among the clamor are ersatz instruments: shattering glass, power tools, and bashing on a tractor-trailer. Crude sampling also plays a role, with fragments of Wagner spliced into the raucous second side.

Though Bubbles plangently proclaimed a trashy aesthetic, some other purpose seems at work with the willful amateurism and noise-mongering. An antecedent may be the Portsmouth Sinfonia, a British classical music ensemble that spanned the 1970s. It welcomed any comers, combining the trained (though on unfamiliar instruments) with rank amateurs. Though their performances were cause for hilarity, the intent wasn’t humor or to mock the music. Participants were directed to perform to the best of their abilities.

Founded by experimental composer Gavin Bryars, the orchestra was a high concept take on music and mastery. Fittingly, the famously untrained Brian Eno joined the ensemble on clarinet, produced their first two albums, and featured them on his Taking Tiger Mountain (By Strategy) track “Put a Straw Under Baby.” Along with his avowed autodidaction in music, Eno often imposed physical and conceptual constraints on studio musicians that interrupted their prowess. His Oblique Strategies were employed in service of fresh attitudes toward music, to foster novelty and sass.

Bubbles’ concept was lower but conveys a deconstructive reverence for the genre. He designed for and identified with the punk and new wavers. Overall, Bubbles had empathy with the misfits, his attitude being (according to Jake Riviera, speaking of Barney’s work for Johnny Moped), “Bring me your dented and out of shape.” Moped and his ilk represented a return to rock and roll’s rough and ready Teddy pre-Beatles roots. Fervor and fun were critical components; maestros could fuck off. It was deadly serious (“We mean it maaaan!”) and flippant (“And we don’t care!”)—all in the same band.

It could be that Bubbles decided to take this sensibility to its illogical conclusions. He’s showing the youngsters how it’s done—or just getting in on the fun. Where early rock and roll was rudimentary by nascence, stripping songs down to their bones was a widespread new wave stratagem.

A frequent aspect of punk and post-punk covers of classics hits was toying with tempos. Rhythms were regularly sped up to a breakneck pace, or slowed to a plod, or tooled to a robotic pulse. In increasing melodicism, there’s Devo’s version of The Rolling Stones’ “(I Can’t Get No) Satisfaction,” (Bubbles designed the Be Stiff EP containing their original recording of the song), Magazine’s frosty Sly Stone “Thank You (Fallentin Me Be Mice Elf Agin),” and the Eno-directed Talking Heads slow burn version of Al Green’s “Take Me to the River.” The songs were veneration and negation in stereo, revealing the artifice of music as pop product and prayer.

Bubbles slightly extended the axis of anti-mastery that punk reanimated, nearer to the desired absurdity. To elude any semblance of commercial viability, he would have to drop below new, lessened standards. In 1979, David Cunningham’s DIY project The Flying Lizards had scored hits with their tinker-toy takes on “Summertime Blues” and “Money (That’s What I Want).” Ersatz resembles a rough, joking demo of either, or the product of a poor mix.

In looking for antecedents to Bubbles’ endeavor, a possible influence—or at least, confluence—may be with an American group with lower-fi, hippier, and deeper roots. That connection combines Ersatz’s two sides and engages the records’ covers.

Side two of Bubbles’ record is comprised entirely of the audio collage “Insolence Across the Nation,” and credited to Imperial Pompadours. Like its first side songs, “Insolence” is sparse; at its busiest it will have competing stereo separated voices over music and sound effects. The effort is less “Revolution 9” than a recording of an absurdist drama.

Bubbles friend and Ersatz performer Nik Turner explained to Paul Gorman that “Barney said he wanted to do something about the life of Hitler…I selected quotations from Mein Kampf, Mad King Ludwig and Wagner and also from the women in all their lives, and then recorded random visitors to my flat reciting them.”

With its Wagnerian bluster and Fuehrer proclamations, “Insolence” abandons all subtlety, abjuring metaphor for blunt force audio trauma. To quote occasional client Dave Edmonds, it’s as subtle as a flying mallet. The sleeve listing for the track indicates it was “recorded LIVE at Krankschäft Kabaret.” Krankschäft was a name subsequently used by a backing band for sometimes Hawkwind singer and lyricist—and Ersatz vocalist—Robert Calvert.

The side fades in on a distant jazzy saxophone-led instrumental that dips under narration. The first voice suggests a fairy or folk tale is about the start. The Mein Kampf quotations kick in around the 10-minute mark, arriving with a jolt and growing increasingly vile. Speakers frequently adopt pompous or cartoonish villainous tones, often undercut by sniggering and snide responses. After a crescendo, the Wagner slowly fades out as the track began.

Invoking Nazi Germany in a rock and roll context was neither unique or original with Ersatz. Nor was presenting fractured takes on pop songs. San Francisco-based avant-gardists The Residents went there years earlier with their 1976 second LP The Third Reich and Roll. That LP mashed together skewed versions of singles and commercials over two side-long pastiches called “Swastikas on Parade” and “Hitler was a Vegetarian.”

Third Reich is entirely comprised of merged mutant versions of 60’s and 70’s popular music (rock, funk, soul, folk) ranging from Count Five’s “Psychotic Reaction” to America’s “Horse with No Name.” While the former is more in line with Bubbles’ obscure tastes, the majority of the 29 songs are classic Top 40 hits, though frequently unrecognizable. Songs can overlap completely, or have components interjected into others. Where Bubbles listed his individual tracks, on its release The Residents left listeners to discern what ingredients made up their sonic stew.

Ersatz and Third Reich and Roll are twinned transpositions of each other on the Nazi aspect. Bubbles loudly places his Hitler content only in the tracks. His sleeve gives no indication of what’s to come. Meanwhile, The Residents’ grooves are devoid of any such references. But the album title and cover imagery prominently invoke the Nazi past. Swastikas abound on the cover, which features a Hitlerized Dick (American Bandstand) Clark.

Commercialization is a career-long subject for The Residents and pop music is a target rich environment for satire. But invoking Nazis blows away any nuance, resulting in camp. Bubbles is as unfocused conceptually with an offering that aspires to be “something about the life of Hitler.” “Insolence” easily clears that low hurdle. It’s an open question if it’s something more.

These were the early Margaret Thatcher years, which galvanized many musical protests. The right wing prime minister’s nationalist, capitalist triumphalism outraged progressives of all stripes. Comparisons to Nazism and fascist states flowed freely. She was supported enough to serve eleven years as PM, and widely reviled. Either side could be tarred as impertinent in their stance.

The parallels between the two albums suggest an awareness. Bubbles traveled to San Francisco in 1978, but there’s no record he had any exposure there—or subsequently—to the Residents. But their arch humor seems just his style.

Bubbles could also be tweaking the fashion choices of certain musicians of the day. Some punk and post-punk acts flirted with Nazi symbols and imagery in ways that weren’t apparently ironic or condemnatory. And the Sex Pistols infamously offered “Belsen Was a Gas” (performed last at their final show—in San Francisco). Naïveté and cheap outrage were criticisms leveled at musicians wrapping themselves in Nazi iconography. Bubbles could be making a blunt retort and providing a schooling in the actuality.

While acoustically disconcerting and in subject matter, “Insolence” is only half the record. Graphically, Bubbles emphasizes the album’s wider sensibility of evoking the past. The sleeve design has a rough equivalence to the music. Both are unstable and convention-challenging.

♭♭

On the surface, the music and design of Ersatz are opposed—another Bubbles contradiction. The design of Ersatz is a characteristically self-effacing gesture for Barney Bubbles. Neither his name or his voice is on it. The package is simple, direct, restrained: a conventionally professional product. Variances are conceptual and considered.

An unruly, David Carson-like expression would be a reasonable expectation for the formal representation of the rowdy Ersatz content. Capability or appreciation for such a manifestation isn’t an issue. Bubbles’ portfolio amply demonstrates he could successfully adopt an anarchic, immediate styling if desired. The entire folding outer wrapper of Armed Forces is a study of coordinated commotion.

A major difference is that Bubbles is solely responsible for the graphic performance. In the design studio, he was an off-the-cuff genius. He excelled under the tightest deadlines and budgets, reduced means, and in crappy quarters. Barney made great design literally out of garbage. On their own, the sound studio games, if transferred wouldn’t bring the same crude result. Graphic dissonance in the Ersatz sleeve had to be subtler.

What aren’t distinct, planned Bubbles quirks are ambiguous, attributable to pragmatic economic decisions or stylistic twists. For instance, though a full-fledged 33 RPM album, Bubbles housed the disc in a flat sleeve meant for 12-inch singles. This confuses expectation of what the nature of the record is.

In keeping with its throwback rock and roll, the package design is back to basics. Absent are extravagances such as die cutting for X in Search of Space or Armed Forces, photography, or even color. The only printing ink employed is black, with selective screening to produce a grey tone. Just as might be seen on albums pre-Sgt. Pepper era LPs, the front cover featuring an image and the reverse consisting entirely of text: the track titles and credits.

Characteristically, Barney puts his portrait on other people’s records, not his. According to Paul Gorman, the cover illustration is a freakish “Elvis Presley in the woodcut style of Flemish expressionist artist Frans Masereel.” The brushed ink and cut-paper King sports an enormously elevated coif that bleeds off the top of the sleeve. The pompadour reinforces the throwback aspect, amplifying a 1950’s era hairstyle.

Bubbles turned to this particular manner of illustration for a number of albums during this time, notably for a portrait of Billy Bragg and the cover for his Brewing Up with Billy Bragg and for Inner City Unit’s Punkadelic. A full-color example can be found with the flautist figure on Imperial Bedroom.

The album title is placed contra-commercially in the lower left-hand corner, as if spoken by the Elvis figure. Its frisky setting is a frequent flourish from Bubbles’ benign typographic trick bag. The “ER” is dropped out of “IMPERIAL” to complete “ERSATZ.” It also forms by subtraction “The IMP”—a little devil. (Jake Riviera and Elvis Costello’s post-F-Beat label was named Demon Records.) All text is reversed out, save for “SATZ,” which is screened to grey. “IMPERIAL” and “ERSATZ” are capitalized—is Bubbles announcing he’s (the) Mock King?

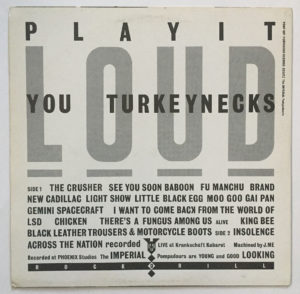

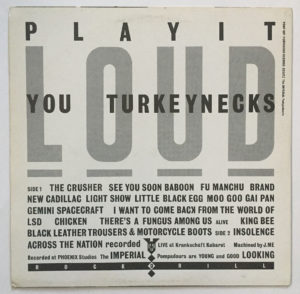

“PLAY IT LOUD YOU TURKEYNECKS” dominates the back cover in large caps, filling roughly 2/3 of the vertical space (the cover figure definitely fits the description in its neck). The words are lifted from the album’s kick off track, “The Crusher.” “LOUD” is the sole text screened grey and placed behind the black text. Each letter earns its own underline to doubly emphasize the command. Minimal legal text (catalog number, label, artist name and album title) run down the upper right edge of this text.

All the text set on the back-cover text is force justified and styled contemporarily, rendered more expressively than the practical layouts of the 50’s and 60’s. That expressiveness manifests solely in arbitrary changes in scale and capitalization. It’s a rough equivalence with the variable volume of elements in the music. The track listing runs the all caps titles together in a force-justified block. The face is a Grotesque, similar is style to that found on the reverse of early Beatles albums (though not exclusively theirs).

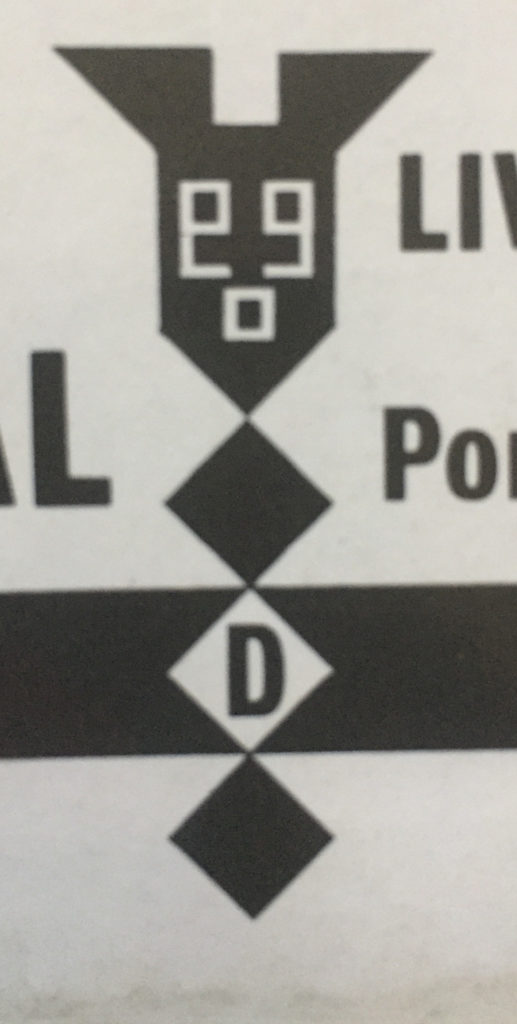

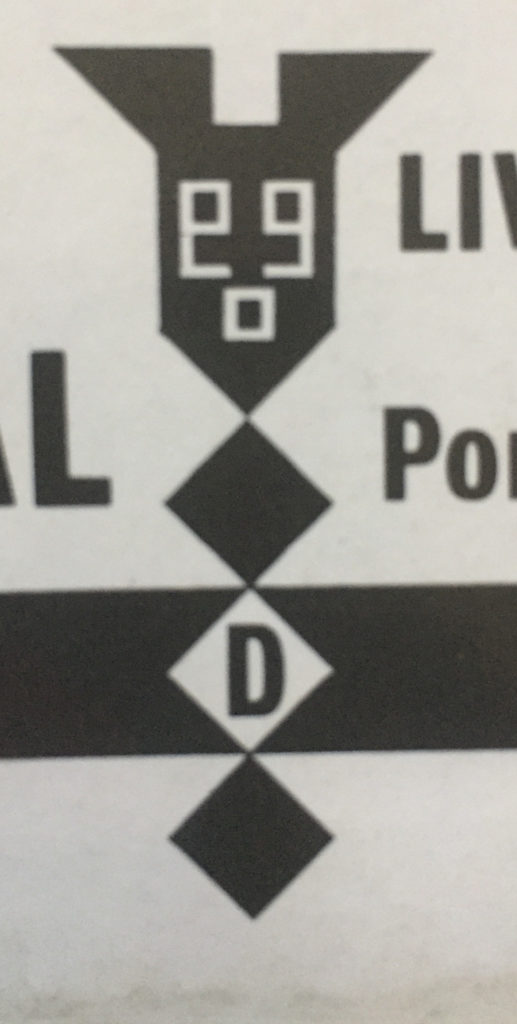

The lone graphic is one of Bubbles’ custom sigils—a stylized screw penetrating a thick black horizontal rule emblazoned with “ROCKDRILL”. The “D” of this word is on the screw’s point. This graphic appears anthropomorphized (as with “Timmy the Talking Toolbox” on the cover of Ian Dury’s Do It Yourself) with a “face”: opposed mirror-image open single quotes over a square/period “mouth.” The trio can also read as “ego.”

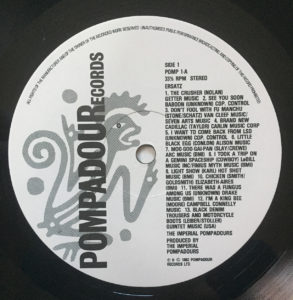

It’s in the track listing that Bubbles visually echoes the music’s instability. He does this primarily by blundering around with titles across the sleeve and record label. The names of songs vary between sleeve and label, sometimes abridged, sometimes not, to no discernable reason. It may just be in service of typefitting, always a challenge with justified settings.

“Fu Manchu” on the cover is “Don’t Fool with Fu Manchu” on the label, “I Want to Come Back from the World of LSD” is abbreviated to “I Want to Come Back from LSD.” Other titles differ in tense: on the sleeve “There’s a Fungus Among Us,” on the label the fungus has moved on. And some are combos: “Gemini Spacecraft” expands to “I Took a Trip on a Gemini Spaceship.” (And rhymes!)

Apart from the dropped title text, Bubbles indulges in minimal type trickery, mostly in point sizes and capitalization. He does horizontally flip the “K” concluding “BACꓘ” in “I Want to Come Back from LSD.” While often fanciful, Bubbles’ typography was always judiciously deployed, never overpowering layouts.

As with the music, why be a stickler with text? Scratch out a clumsy guitar solo; scribble down titles on scrap paper. On the radio or in concert, they don’t always announce the song titles, or they mess them up—who cares? What matters is how they sound, bro. Which is better after a few brews, honestly. These guys might consider rehearsing sometimes before hitting the stage. So “Light Show” (a wink about his alias and early career?) and that LSD song are flipped on the cover—it’s straightened out on the label. Are you hear to rock or proofread?

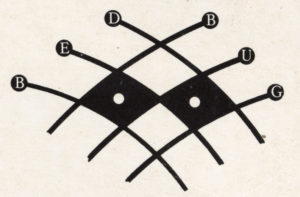

The package comes with a plain inner sleeve but includes a bespoke record label extending the cover theme. Labels have black text on a solid white background. The face used throughout is an all caps bold condensed Univers, a regular BB choice for this usage. It’s also used for a simple wordmark that features one of his shared character type treatments that forms “POMPADOURECORDS.”

Screened to grey behind this vertically-reading text is another illustrated figure, which may be meant as the Pompadours Records logo as it’s repeated. This line drawn creature—monkey? (one song is “See You Soon Baboon”) Lizard? It boasts a curled tail—wears another wacky ‘do. The simianewt is open-mouthed as if singing or shouting, arms raised with pointed index fingers as if dancing or proclaiming. It looks askance at us with a solid black pupil.

In what may be a nod to his musical co-conspirators, the package has similitude with Inner City Unit’s first LP, Passout (RI¿¿LE Records, 1980). Rather than devise a grandiose or unique cover, it fits in with his overall direction in sleeve design at the time. He didn’t place himself above or apart from his clients.

♭♭

Bubbles’ training was Modernist and he was an articulate student of design history. The total designer spread his sensibility into all creative forms. With Ersatz, Bubbles could now claim music with art, design, furniture, and video. A record was inevitable.

Across all his work, in all media, is the elevation of the mundane, a collapsing of low and high cultures, historical forms re-imagined and re-contextualized, the integration of found materials, humor, adventure…and games. He worked fast, made do, and reveled in and revealed with it. Accident was embraced and incorporated. Tangents followed. Answers and identity withheld.

Ersatz isn’t the key or the masterpiece but a synopsis of Bubbles’ design, the order and the anarchy. In the end, listening to Ersatz isn’t as satisfying or elevating as experiencing his other media, especially the design. After many listenings, it’s growing on me (which may be more a testament to the songs than the performances), slowly revealing not secrets but the consistent question of his work.

Is this a real record? Isn’t it just a one-off vanity project, a goof, for patrons that specialized in these kinds of things? Real in art usually means more. Is that a real measure of something’s truth? That you’re able to repeat yourself? (What about say something once, why say it again?)

We’ll never know if there was an intended follow up. Are there more songs in the can? It’s not like your typical band’s first release, and Ersatz just contains all the best songs from their stage repertoire.

Everything about the record says one and done. Ersatz may exist just to exist. To be a real record, it had to have sounds on it, so Barney made some, having the most fun he could. It’s the purest expression of his work as there was zero pressure to make a hit. Don’t care for it? Hey, the record’s title announces there’s better elsewhere.

Barney Bubbles’ work always seems to prompt the question: Is he (for) real? The fucked-up quality of this record begs cult status—a feature for him, not a bug. The anonymity and pseudonyms (does he really exist?) undermines his career. The graphic games, puzzles, secret meanings, variations—all commercial poison.

Bubbles never resolves the essential conflict of making a living doing something you love. There’s a real romanticism to this willful contrariness and obscurity, in the work and the person. He just can’t help himself. Bubbles should have been famous and may get there yet. But alive, he was having none of it.

Ersatz is real, it just isn’t right. Ersatz is both. So, if you’re in the market for Barney Bubbles, dis-order now! Ask for him by names. Accept all substitutes.

♭♭

“No one I know, including myself, has listened to it all the way through. It is not meant to be.”

—Lou Reed, original liner notes to Metal Machine Music (The Amine β Ring) (RCA, 1975)

♭♭

Note: This is the third part of my ongoing study “Barney Bubbles: Offset Identities.” The previous two can be found in the “Writing” section. These essays draw from Paul Gorman’s book Reasons To Be Cheerful: The Life and Work of Barney Bubbles (Adelita, 2010) for details and quotes about Bubbles’ life and work.

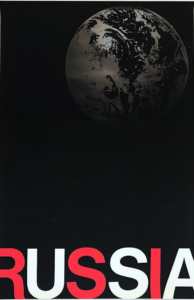

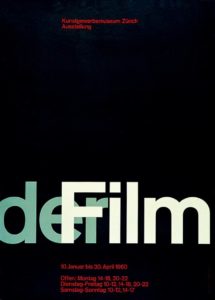

A comparison of Der Film and Russia, USA Peace is instructive. Both are signature works of the respective designers. The core aspect of each is a depiction of an effect of light: Casey using varnish, Müller-Brockmann an overlap that implies light projected through a transparency.

A comparison of Der Film and Russia, USA Peace is instructive. Both are signature works of the respective designers. The core aspect of each is a depiction of an effect of light: Casey using varnish, Müller-Brockmann an overlap that implies light projected through a transparency.