On Stefan Sagmeister’s Things I Have Learned In My Life So Far

The arguments these artists mount to the detraction of beauty come down to a single gripe: Beauty sells, and although their complaints usually are couched in the language of academic radicalism, they do not differ greatly from my grandmother’s haut bourgeois prejudices against people “in trade” who get their names “in the newspaper.” Beautiful art sells. If it sells itself, it is an idolatrous commodity; if it sells anything else, it is a seductive advertisement. Art is not idolatry, they say, nor is it advertising, and I would agree—with the caveat that idolatry and advertising are, indeed, art, and that the greatest works of art are always and inevitability a bit of both.

—Dave Hickey, “Enter the Dragon”

Gonna make you, make you, make you notice

Gonna use my arms

Gonna use my legs

Gonna use my style

Gonna use my sidestep

Gonna use my fingers

Gonna use my, my, my imagination

‘Cause I gonna make you see

There’s nobody else here

No one like me

I’m special, so special

I gotta have some of your attention—give it to me

— Chrissie Hynde, James Honeyman-Scott, “Brass in Pocket”

I like Things I Have Learned In My Life So Far. As a showcase for previously released Sagmeister material, it’s an improvement over Made You Look. However, the compilation aspect is a minor similarity between the books. The focus exhibited by Things can be partially attributed to presenting a themed series of works. But Sagmeister also continues to come into his own as an artist. So much so, in fact, that he deserves his own category: hyperdesigner.

What’s significant about Sagmeister’s work, and makes him a “hyperdesigner,” is that he’s not very original, as that term is classically used. He lifts freely from a wide range of designers and artists (in this book, he channels his post-Hipgnosis sensibility through Ed Ruscha). Sagmeister recognizes that the history of art is a history of appropriation and adaptation. And, more importantly, that graphic design is now a distinct language operating in culture, with its own idioms, tropes, and representations. Hyperdesign is graphic design taken to a higher level, self-aware and self-referencing.

This is one way that Sagmeister represents another crisis for the Modern movement in design. He’s jettisoned or contradicted nearly all of Modernism’s directives, not out of a contending doctrine but simply because it’s dull and confining. Never mind your literacy-warrior typography and “ugly” graphics; it’s Sagmeister who’s killed off the Modern design movement—with kindness.

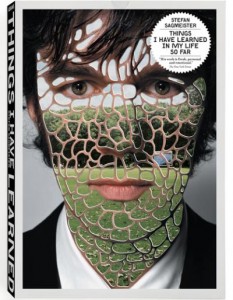

Things is not a standard codex (a given) but more a variation on the AGI/Mike Doud/Peter Corriston package design for Led Zeppelin’s 1975 LP Physical Graffiti. Instead of that package’s New York tenement, here you peer into the die-cut head of Sagmeister.

The cover concept is so simple it feels patronizing to explain it. Within the sleeve are 15 separate booklets with different cover designs that may be shuffled to the front to produce a different pattern within the designer’s face. Each of the booklets features a typo-pictorial staging of one or more of 21 declarations of things Sagmeister has learned in his life. Most are fairly self-evident (“Everybody (always) thinks they are right”), some ironic (“Trying to look good limits my life”), some I’ll have to take his word on (“Material luxuries are best enjoyed in small doses.”)

The dramatizations (“illustrations” is too meek a term) of the statements are a catalog of visual representations. The book is the print equivalent of a David Byrne mix tape: a cumbia followed by a New Orleans brass band next to an North African chant before an chamber orchestra work alongside some funk. Sagmeister will perform his own compositions (for instance, shaping words himself out of AC ductwork or twigs), or step aside for guest soloists (Marian Bantjes forming words out of sugar).

Things is a testament to eclecticism and where Sagmeister lunges down Modernism’s throat and yanks it inside out. His formula to relate to the broadest possible audience is kaleidoscopic stylistic variety. Rather than synthesizing the Universal, he’s asserting subjectivity as the way to communicate widely and accurately. If Sagmeister indulges himself, he connects with you. In his quest to not be boring, the only boundaries are his personal taste. Otherwise, Things is a triumph of “it works if you make it work.” Everything is up for grabs.

Beyond the cover sleeve, no attempt is made to relate the statements with its attendant imagery. Disconnection is the declared strategy. Significantly, it’s here that Sagmeister gets wobbly in his justification: “Even though I am, in general, not a big fan of ambiguous design (“the viewer can take whatever she or he wants”), in this instance I thought I would leave the system open and create room for the audience to relate.” This rationalization suggests the need for a 22nd statement: “Don’t make distinctions without a difference.” Sagmeister’s design may not always look like a Cranbrook special but it’s quacking like one.

The sentiments that the book is built around are simultaneously heartfelt and meaningless. They’re textual hangers to drape the graphic indulgences upon. Sagmeister possibly sees his salvation from Ambiguous purgatory in the ordinariness of the phrases: no clever word play, puns, or double meanings. Sagmeister’s list may also push back against a perceived pressure to be “serious” in his work. Someone else (like critics?) wants him to have a (gulp!) theory. No thanks, he’ll just pull something from his diary and run with it.

For a picture book that isn’t a monograph, Things is damn wordy. In addition to Sagmeister’s extensive explanatory texts, the book boasts three guest essays. Psychologist Daniel Nettle, Guggenheim Museum curator Nancy Spector, and omnipresent design writer Steven Heller contribute tracts in their specialty areas (happiness, art, and writing genial forwards to design books, respectively).

Since the featured imagery is being reprinted for the book, Things can be regarded as a “making of” documentary. Sagmeister’s text resembles a director’s commentary track on a DVD bonus disc. His attention is almost exclusively on technical details and anecdotes. The text has no more in-depth analysis of design than found in a typical issue of Print (i.e. none).

Sagmeister proclaims that the book’s intended audience is non-designers. Evidently, they appreciate—or require—voluminous liner notes. Sagmeister prefers the books where the designers get chatty. And the popularity of those behind-the-scenes DVD extras supports a populist approach. However, this being a book of graphic design raises the question of explicatory overkill—if not negation.

Perhaps this is simply my personal preference to enjoy work without the artist constantly whispering in my ear. (I’m still of two minds about printing the lyrics of songs in albums and CDs.) I feel I may almost trust Sagmeister’s work more than he does. A real area of risk may be for him to restrain his impulse to coat his work in a syrup of “talk normal” banter. Save it for the lectures.

The voluminous text points out another schema in the book. Why trot out Spector and Heller to speculate on Art and Design if you’re not up to something? The weightiest aspect of the text is ruminations on the relationship of those two disciplines. Sagmeister introduces the topic then, unfortunately, hands off to Spector and Heller. Of the three, Sagmeister is briefest but has the best grasp of what’s going on culturally. His exceptional instincts lead him to the essential truth; art and design differ only in the segment of the marketplace in which they operate. The essential activity is the same. They just answer to separate validating structures.

But what Sagmeister gets wrong isn’t really his own claimed insight. Usually, his art borrowings have merit. Here, however, Minimalist sculptor Donald Judd is approvingly quoted that “Design has to work. Art does not.” Going to fine artists, however well respected for insight on their art, is the last place to visit for reliable commentary on graphic design.

That fine art is relieved of the necessity of actively pleasing an intruding clientele would be news to Christoph Büchel or Richard Serra.

Of course, it all depends on what your definition of “work” is. Much of the design in this book “worked” no harder than a Judd piece. Sagmeister’s clients have gone from agreeable (some rationalized connection of client content to the panoplies is required) to indulgent (“do whatever you want”).

His briefs were open-ended. The clients were buying “a Sagmeister”—not commissioning a graphic designer. Wrangling over matters such as budget, siting, and content is typical for art installations. And though art buyers may not specifically commission an artist to make a kind of work, they regularly place demands on the type of piece they’ll purchase. They also return art to the gallery without qualms.

Sagmeister, usually a voice of sense and sensibility about art, here takes an uncharacteristically romanticized view of the enterprise. It’s puzzling why he bothers to wade into the morass at all. He should trust his instincts and not differentiate. It unfortunately leads him on a path away from his full potential as a transformative figure.

Not that he’s actively applying for the job. He’s too savvy to get bogged down in grandiose gestures. Every aspect of his work is downplayed and soft-pedaled. He admits the statements making up the book are “almost banal.” The whole project began as a spontaneous riff, initiated under deadline pressure. In the contemporary coinage of non-admission concession: it is what it is.

Sagmeister is refreshingly self-effacing and upfront about his ambitions. The extravagant claims come from the textual hirelings (I’m making them for free!). One claimant is psychologist and author Daniel Nettle. His essay on happiness is fine until it specifically addresses Sagmeister’s phrases. Nettle inflates their meaning more than they are worth. While it’s good that scientists are studying happiness, the reported findings aren’t exactly revelatory. They easily fall into the category of reports like “Men are attracted to women they find comely.” (But now we have metrics!)

Nettle means well but overstates the case. An artist keeping a diary with reflective thoughts isn’t headline news. Despite this, Nettle comes close to having a point if he juxtaposed Sagmeister with fine artists over the emotional tenor of his work.

Art for the last century, and contemporary art in particular, continues to scorn aesthetic pleasure and emphasize the baser instincts and actions of humanity. To use a generalizing, musical metaphor, art regularly embraces atonality. Graphic design promotes melody. Uplifting messages in art grow scarce and suspect as you get to the rarified heights of the field.

To cast aside the joy aspect of human existence is plain dumb. Though it usually does so clumsily, graphic design has carried a banner of beauty (with an effort like “Cult of the Ugly” being the clumsiest). Sagmeister’s dogged pursuit of happiness is a welcome contribution to a pleasurable counterforce.

If there’s an artist that Sagmeister resembles, it’s Yoko Ono. Her work is frequently simple and affirmative, making it stand out in the avant-garde art world (which was an initial attractant to the oft-cynical John Lennon). I treasure my copy of Ono’s A Box of Smile, a small plastic container, that when opened, reveals a mirror at its bottom. The piece rarely fails to generate the intended reaction. Simple, commercial, insightful (literally!). And with famous works such as Cut Piece, Ono was willing to make her self part of the art. Being cut also figures prominently in Sagmeister’s portfolio.

The essayists who speak directly about Sagmeister and art are Nancy Spector and Steve Heller. Despite the fact that Sagmeister consistently insists that he’s not making art but graphic design, Spector offers an art history lecture on artists dabbling in the advertising/print world.

Spector’s discourse on these art movements is irrelevant. It’s not the lineage Sagmeister’s coming out of. Her comparisons serve only to demean the designer’s real, relevant activity. Spector can’t get her mind around graphic design being substantive in its own right. Only when it resembles what “real” artists do does she count it as deserving recognition. A telling comment is when she labels Sagmeister a graphic designer “extraordinaire.” This precious term smacks of condescension. Would Frank Stella be called a “painter extraordinaire”?

Conversely, Steve Heller simply doesn’t get art. He repeatedly commits a fundamental art critical error: drawing comparisons based on surface similitude. In the course of three pages, Heller stumbles through 20th century art to align Sagmeister with Futurism, Dada, Fluxus, environmental art, conceptual art, word art, Pop Art, and his own contra-historic confection, the “epigram school.” At that pace, he may as well have continued on to Surrealism, neo-Geo, Lettrism, concrete poetry, or neo-Pop (to name a few). Heller’s effort is not to provide insight as much as encrust Sagmeister with high-art accolades.

Incredibly, Heller dedicates only a sentence fragment to associating Sagmeister with something or someone specific in graphic design (Tibor Kalman). No other reference to the field is made—no mention of design movements or philosophies. From Heller’s text, a reader should assume graphic design to be a homogenous, ahistorical practice, bereft of any significance when discussing its most storied contemporary practitioner.

Actually, one other explicit design reference is made: to the Heller-led SVA “Designer as Author” program. The ostensible design critic and historian remains uninterested in separating self-promotion from criticism and scholarship.

If Sagmeister is to be linked to the contemporary art marketplace, more relevant artists can be found than those presented by Spector and Heller. Sagmeister’s confessional nature suggests Gillian Wearing’s Signs that Say What You Want Them To Say and Not Signs that Say What Someone Else Wants You To Say (1993). Her title is an apt summary of Sagmeister’s entire project.

Wearing’s photographic series documents people she met on the street holding handwritten signs expressing their chosen thoughts. They are simple expressions of individuality, and the tension between private life and public display. They’re also exercises in giving—and getting—voice in contemporary (media) culture. Sagmeister stands in for Every(wo)man in his work, while Wearing puts her/him center stage. Both projects feature bland statements that are made profound (and strange) by their presentation. An additional spin on the art/design/commerce interplay comes with the “appropriation” of Signs for a Volkswagen ad campaign (among others).

The greatest failing of Spector and Heller’s essays is that they don’t question the popular conceptions of art and design. As it would require them to question their own establishment views, it’s no surprise they go the traditional routes. For them, artists remain privileged for their experiments in the design realm, over graphic designers. The assertion is exactly backwards. Sagmeister isn’t inserting himself “unabashedly” anywhere he hasn’t always been. At the least, he’s reclaiming usurped territory and showing them how design’s done.

An oft stated failing of graphic design is that it must derive meaning from some other source. Graphic design can only be the means to a meaning. This supposedly holds it back from being a fine or even liberal art. But Sagmeister’s work suggests that graphic design may, in fact, be able to stand on its own. Of course, we must open up our definition of “meaning” even further than we have so far.

Paint is long established as having meaning as paint. Abstract painting is where the vehicle became the driver. Why not graphic design? A unique aspect of graphic design is its manufactured, multiple nature. The various material effects—inking, varnishing, die-cutting, paper stocks, embossing, bindings, et al—are expressive in consumer culture. They are extensions of physical representations such as a rough paper edge signifying “immediacy” (“torn from today’s headlines!”)

Sagmeister’s métier is exploiting and celebrating these mechanically generated production effects. Though he’s regularly noted as not having a signature style, this exploration of physicality is essentially the same as style. He’s not the originator (Peter Saville and Ben Kelly’s sleeve design for the first Orchestral Maneuvers in the Dark LP is the purest example) but has made it his distinct expression.

So, the popular estimation of Sagmeister in the design profession is right on: he’s an artist as a graphic designer. Unfortunately, he continues to be mis- and over-praised by an insecure field stuck on the Modern conception of “originality.” (See Peter Hall’s text for Made You Look for the definitive example of this.) Sagmeister doesn’t do anything new. He does better: wringing new articulation out of timeworn graphic dialects.

A subject for concern is if Sagmeister abandons the public art aspect of graphic design. To do so would be to echo art’s service of exclusive clients. Forms may change but the framework of capital remains. Sagmeister’s insistence to be counted within the populist medium of graphic design is negated if his artifacts are estranged from a mass audience. “Blurring the boundaries” is a meaningless, restricted diversion if the design market economically functions the same as that of art.

What is potentially transformative is if Sagmeister challenges the connection between elite practitioners and the moneyed culture. As a producer of rarified commodities, he’d be just another facilitator of celebrity and capital. Good for him if he breaks into the art market. But will it be a triumph of stardom and networking, or graphic design?

Things is a positive indication in that regard. It’s Sagmeister the designer, making signs to and for everyone, out in the everyday world, not being boring, generous and mischievous. It’s more fun than “art,” and, perhaps, better for you.

Note: This essay is adapted from the curatorial text (in progress) for an exhibition of Stefan Sagmeister’s work to be held October 18–November 23, 2008 at the Baron & Ellin Gordon Galleries of Old Dominion University, Norfolk Virginia.

Wow. Very nice. I think the highwire act of balancing the respective discourses of art and design is nicely done. _Very_ nicely done.

http://www.creativereview.co.uk/crblog/things-i-have-learned-in-my-life-so-far/

What a great article. A stimulating analysis of design in the context of art and modernism. I particularly get a kick out of the hyperdesign terminology and its reference to semiotics.

Nice read. The heady Art vs Design notion is neither here nor there. Nor entertaining or relevant as to what Chrissie Hynde was getting at.

There’s a hilarious review of this book by Douglas Coupland in I.D. Magazine you should check out. He gets some good riffs in.

http://www.id-mag.com/article/Sagmeister/

Coupland’s review is great, and coupled with this one, a great barometer of graphic design right now I would say.